- 01 Luk Lak Wamena Nen Asep Nayak

- 02 Ap Apikon Ane Asep Nayak

- 03 Pikalu Haqmare Asep Nayak

- 04 Adug Werek Negen Nerop Asep Nayak

- 05 Aworok Werek Negen Asep Nayak

- 06 Nayaklak Werni Wamena Aworok Haok Nen Asep Nayak

- 07 Bujuk Tidur Asep Nayak

- 08 Nayak Nen Hamare Nerop Asep Nayak

- 09 Erogar Nerop Asep Nayak

- 10 Aweleken Milaq Asep Nayak

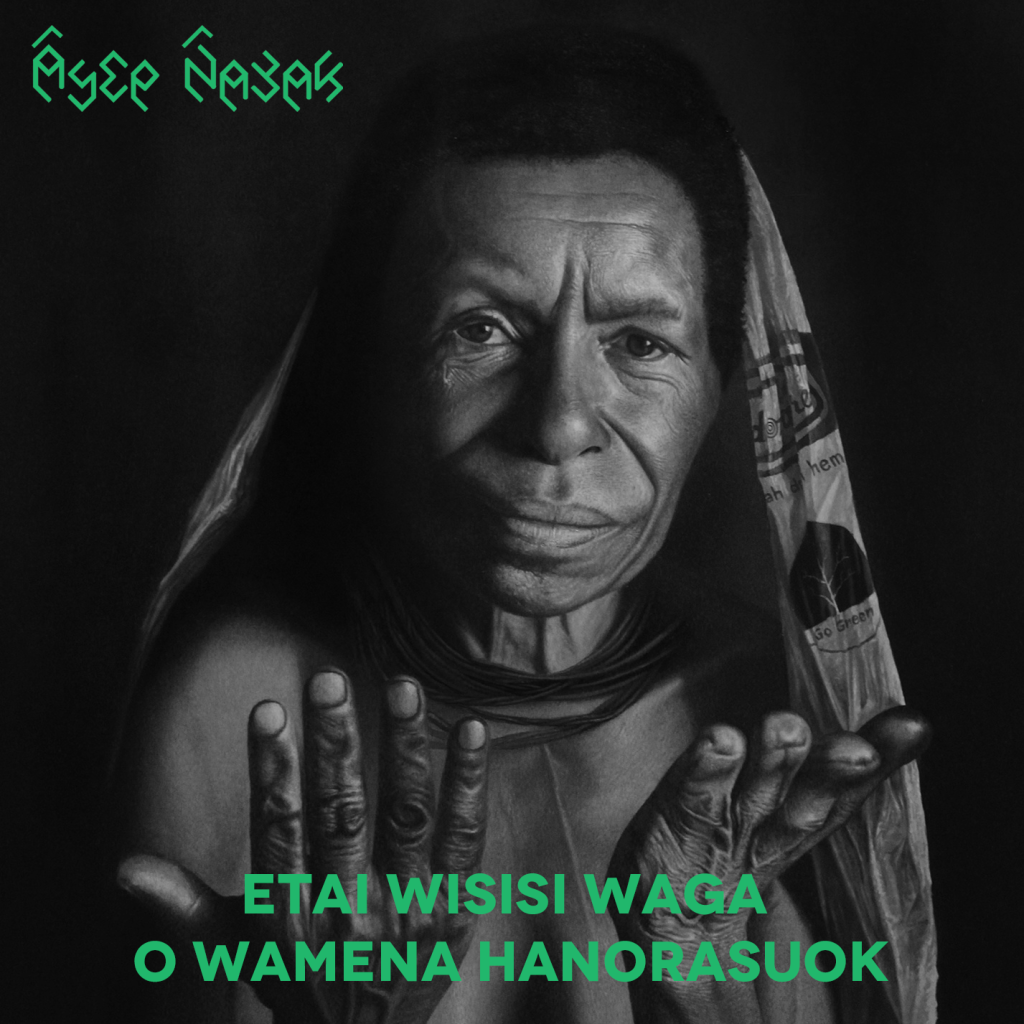

Liner Notes

You don’t talk to Asep Nayak and peg him as a dance music provocateur. Timid, soft-spoken, and disarmingly polite, he’s more a reflection of his daytime self: a 22-year old with wildly varying interests struggling to graduate college. Drag him to any dance floor in the highlands of West Papua, though, and the kid turns into a star.

Except it won’t look like your garden variety dance gig. The music is fast paced, relentless, almost trance-inducing. A flash mob of men and women who barely know each other join forces in a choreographed dance routine they are instinctively familiar with. Meanwhile, a pair of small, rusty speakers are blaring music sourced from communal USBs or laggy Youtube connections.

Forget everything you think you know about dance music. Welcome to the world of wisisi, Wamena’s dance dance revolution that’s ready to take the world by storm.

Barely attempting to hide his giddiness, Kasimyn breaks into glorious laughter. “This is just pure dance music, man.”

The story begins in Wamena, a town situated in the highlands of West Papua. Pushed to the margins even by West Papuan standards, the region is popularly associated with natural disasters, civil strife, and intermittent clashes between government forces and pro-independence fighters. Fertile ground, then, for electronic dance music.

Nikolas Surabut was barely thirteen years old when he began getting bored of traditional wisisi, a ritualistic music and dance often performed at harvest ceremonies, funerals, and weddings in the valleys of Baliem, deep in the mountains of West Papua. “You couldn’t really record these performances for posterity,” he said, speaking from his home in Wamena. “They play tonight, the entire village dances, but tomorrow all we have left are stories. I wanted something that would last longer.”

It was 2009, and the youthful Nikolas began consulting older friends who he knew “made music with computers.” They directed him to a catch-all music production software: Fruity Loops Studio, popularly known as FL Studio. Light, simple to use, and easy to pirate, the software became the weapon of choice for aspiring music producers working with a limited budget and even more limited hardware.

“My friends were mostly making reggae and hip hop with FL Studio,” Nikolas said. “I wondered if I could use FL Studio to recreate wisisi instead.”

A keen musician himself, Nikolas began breaking down the basic tenets of wisisi: a wooden, lute-like instrument Nikolas was well-versed in; pikon, a mouth harp made out of bamboo with a similar trance-like quality to the didgeridoo; and tifa, a percussion made out of wood and dried leather, ubiquitous in many Papuan cultures.

“I tinkered with FL Studio and laid down beats inspired by tifa,” Nikolas said. “But mainly I was looking for sounds that best emulate the sounds of our wooden guitar.”

The end result was a masterpiece in taking tradition apart and moving beyond its constraints. Wisisi’s repetitive, mantra-like chants are recreated faithfully, but its middling tempo is set aside for furiously quick, propulsive beats. Each song is barely two and a half minutes long, with the traditional guitar melodies reworked into intricate rhythm sections and interlocking percussion. The cherry on top, of course, are the painfully retro robotic shouts and ad-libs scattered intermittently throughout the song.

“The great thing about FL Studio is that the final product is already in mp3 format,” Nikolas said. “So it was easy to move the songs to my phone and play them for my friends.”

Nikolas set to work, insisting on playing his newfangled compositions at student protests, weddings, fundraisings, and his local hangout spots. “My music spread from phone to phone, peer to peer, hangout spots to hangout spots,” he recalled. “You hear it at a party, and if you like it, you download it from the host’s phone. Slowly, it spread around Wamena.”

One of the earliest converts was Asep Nayak. Only two years Nikolas’ junior, Asep heard the now-grizzled pioneer’s music at a birthday party and was captivated. “When they played wisisi, the dance floor erupted,” he recalled. “I wanted to make this kind of music. So I asked around to my friends.”

Unlike Nikolas, he was no prodigious guitar player. He came from a stoic, deeply religious family, and was more renowned to his friends as a talented football player rather than a musician. Asep persisted, though, and began uploading his music through a newly popular video platform: YouTube.

Even today, the mantra persists: Nikolas made it first, Asep second. The pair’s teenage kicks steadily infused Wamena’s party scene, supplanting genres beloved by its youths like reggae and hip hop.

Don’t imagine them taking over the DJ booth and performing live like any musician, though. Wisisi musicians are less live performers and more portable jukeboxes ready to take any party by storm. They would bring their music over to roadside stalls, birthday parties, hangouts, and beachside barbeques on their phone or USB stick. Someone somewhere will inevitably bring active speakers, the phone or USB stick is plugged in, press play, and cue pandemonium.

All the traditional norms of popular music are thrown out the window. For one, there are no fixed titles for any song. Cursory searches at Asep Nayak’s Youtube history will reveal bewildering titles such as “Music Wisisi Wamena”, “Music Wisisi Baru”, and “Wamena Wisisi Slow”, while Nikolas’ repertoire contain the unhelpfully-named ditties “wisisi terbaru 2021 (1)” and “wisisi terbaru 2021 (4)”.

There are no wisisi music festivals. Nobody has an “album” of any kind. There are no record labels. There are no fixed collective, crew, or established scenes. There is no formal copyright at play, no royalty scheme or even a fleeting desire for professionalism. The party is free, the music too, and the drinks there are strong and unrelenting.

Simply put, wisisi is music as popular anarchy.

Wisisi’s reputation as the domain of mountain dwellers are eroding fast, with his newfound popularity landing him performance spots in the bright lights of Jayapura, West Papua’s biggest city. “I was invited to perform as a DJ in Jayapura recently, and when I played my music, both their speakers caught fire!” Asep said, laughing. “They can’t handle this music. They don’t know what they’re doing yet!”

Nikolas and Asep believe that in time, the world will wise up to wisisi. “Even people from Wamena sometimes don’t understand this music, especially if they’ve been away for a while,” Asep said. “But they will love it. They learn the dance. They take the music on their phones. And when they meet the diaspora elsewhere, they will lead the party. Eventually it will spread.”

“If you play wisisi, people will drop their work and rise from their beds,” Asep claimed. “Come to Wamena and find out for yourself.” — Raka Ibrahim. This article previously published in Jakarta Post 2021.